Trail to Oregon by J.D. Adams

The origin of the name Oregon has been obscured by the patina of history. Was it born of a mapmaker’s error, or as some believe, a derivation of the French Ouragan, referring to the “stormy place” of the Columbia River? Perfectly elusive, the source of the word Oregon swims in mystery where present scrutiny cannot touch it. The name rolls from the tongue with an airy lightness, yet it carries the understated power of an Indian legend.

Shining with utopian beauty, Oregon is a beacon for those seeking to find their own way to freedom. Looming large is the legacy of the Oregon Trail that defines an unfolding story. In 1848, William Lysander Adams was one of hundreds of emigrants trekking westward that year. He packed his library across the Oregon Trail, and descended from the flanks of Mt. Hood on the Barlow Road into the Willamette Valley to become a pioneer preacher, a teacher, and later a statesman. What made Oregon home for the early pioneers is still a motivating force to later generations; the solitude of the countryside, never far from the sound of water. In the fertile valleys, windy fields and rolling oak savanna, dark grottos of greenery bristle in a patchwork shaped by ancient fires. On the horizon, the Cascades are rimmed in snow, thrusting glaciers into the clouds. The wind carries the promise of autumn on long summer days, mixed with the soft music of the river gliding toward the sea. It is this picture of paradise that keeps the dream alive.

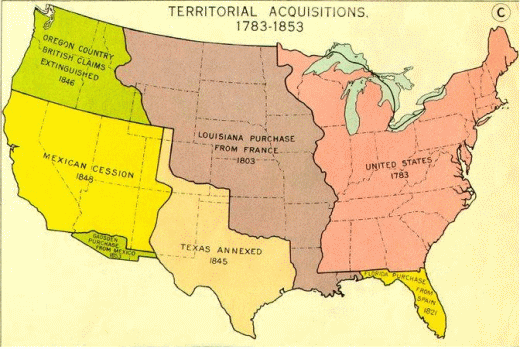

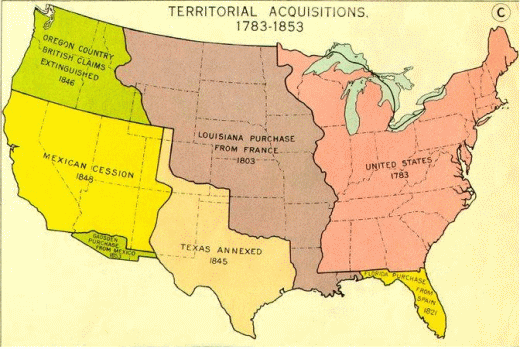

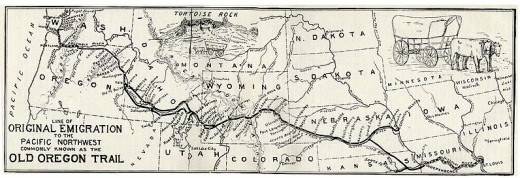

The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolutionary War with Britain, extending the boundaries of the Unites States to the Mississippi River, and pushing the frontier into the Midwest. Mountain Men seeking beaver pelts were among the first to penetrate the Oregon Territory before 1841, followed by Missionaries. An expanding population and the need for economic and religious freedom set the stage for the Oregon Trail migration beginning in 1841-1843. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson organized the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804 to explore the areas west of the Rocky Mountains, including what was known as the Oregon Country. In the Oregon Treaty of 1846, the British ceded the Oregon Country to the United States, and it became the Oregon Territory in 1848 by an act of Congress. The Donation Land Claim Act, which granted free land in the Oregon Territory, was enacted by Congress in 1850.

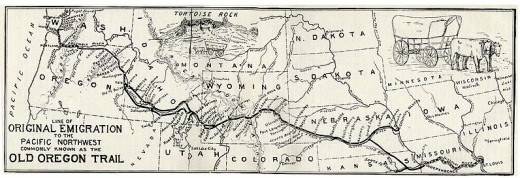

The town of Independence, strategically located on the Missouri River and the Santa Fe Trail, was the starting point for many emigrants on the Oregon Trail. In later years, overuse and a cholera outbreak in Independence led to jumping-off places farther up the Missouri River gaining popularity, such as Westport, Liberty, St. Joseph, Weston, and Council Bluffs. Oregon Trail Pioneers generally followed the Santa Fe Trail into Kansas until a fork in the trail appeared; graced by a modest sign that cast the emigrants into the journey of a lifetime with only these words, “Road to Oregon”.

“My sister and I ascended to the summit of a hill and with the aid of a spy-glass took a farewell view of St. Joe. and the United States. Abigail Jane Scott, 1852”

The iconic covered wagons of the Old West are one of the most revered images in American history. Inspired artists of the Oregon Trail such as Albert Bierstadt have captured the wagon trains with a palette of light and intimate landscapes that invited exploration. The prairie schooner of the Oregon Trail was a specially adapted version of the mover’s wagons that found favor with the settlers of the eastern states of 1783 in progressing distances of two hundred miles or less. The typical Oregon Trail wagon was half the size of a Conestoga wagon at roughly ten feet in length, although a good percentage were actually sturdy farm wagons outfitted with a cloth cover, made often of hemp, and waterproofed with linseed oil.

The well-made wagon employed a box and wheels of hardwoods including oak, elm, ash, and ribs of hickory to support the canvas top. The rear wheels were rather large; almost 6 feet tall, the front wheels were made smaller for easier turning, and all rimmed in iron. The wheel hubs were conical and also reinforced with iron, part of an axle and pivoting frame that was flexible and lightweight. On one side of the wagon was a water bucket, on the other side a toolbox. A lever for braking was accessible, and a trusty pail of grease swung from the rear axle for maintenance of dry bearings.

In the midst of the overland migrations, guides for the traveler became popular, such as The Prairie Traveler Handbook printed in 1859. It advised to be taken for each grown person on the Oregon Trail: “150 lbs. of flour, or its equivalent in hard bread, 25 lbs. of bacon or pork, and enough fresh beef to be driven on the hoof to make up the meat component of the ration; 15 lbs. of coffee, 25 lbs. of sugar, also a quantity of yeast powders for making bread, and salt and pepper.” These are the chief articles of subsistence, to be used with economy and reserved for the western half of the journey. Mountain Men and prairie travelers alike could subsist on foods borrowed from the Native Americans, as described from the guidebook, “Pemmican, which constitutes almost the entire diet of the Fur Company's men in the Northwest is prepared as follows: The buffalo meat is cut into thin flakes, and hung up to dry in the sun or before a slow fire; it is then pounded between two stones and reduced to a powder; this powder is placed in a bag of the animal's hide, with the hair on the outside; melted grease is then poured into it, and the bag sewn up. It can be eaten raw, and many prefer it so. Mixed with a little flour and boiled, it is a very wholesome and exceedingly nutritious food, and will keep fresh for a long time.” Fruits and vegetables which were first pressed and then dried were also found on the plains to be quite flavorful when rehydrated. Another staple from the southwest was cold flour, a mixture of corn meal, sugar, and cinnamon, which could be mixed with water for a quick meal.

“Independence is a handsome flourishing town with a high situation.... The Emigrants were encamped in every direction for miles around the place awaiting the time to come for their departure. Such were the crowded condition of the streets of Ind by long trains of ox teams, mule teams, men with stock for sale, and men there to purchase stock that it was all most impossible to pass along....” James A. Pritchard, 1849

The trip to the Oregon Country usually began on a high note, with socializing and sightseeing, and then settled into the daily routines; on the trail by 7, a cold lunch at 12, progress was 15 miles on a good day. The ride in the wagons was rather bumpy so most preferred to walk. Alcove Springs was one of the first landmarks, a rock formation next to the Big Blue River, where many emigrants etched their names. From Kansas the Trail angled through Nebraska and encountered the Platte River at Fort Kearney. The Platte would be the guiding influence through the plains, through Ash Hollow, where wagon ruts are still visible, and past the evocative Courthouse Rock. Unfortunately, through this spectacular scenery the slow-moving water of the Platte River contributed to the spread of cholera, which claimed the lives of many travelers on the trail from severe dehydration.

After another fourteen miles is a landmark known as Chimney Rock, perhaps the most well-known spire of the American Midwest, now eroded somewhat from its former heroic proportions.

“...if a traveler were not convinced that he is journeying through a desert where no other dwellings exist ... he would be induced to believe them so many ancient fortresses or Gothic Castles, and with a little imagination, based upon some historical knowledge, he might think himself transported amid the ancient mansions of knight errantry ...” Fr. Pierre-Jean DeSmet, S.F., 1841

“We are now in sight of ... Chimney Rock ... which can be seen at the distance of thirty miles. It is two miles from the river, ...and from its peculiar form and entire isolation, is one of the most notorious objects on our mountain march.” William Marshall Anderson, 1834

The emigrants crossed into present-day Wyoming and passed by Fort Laramie on the way to Emigrant Gap, where the Oregon Trail overlapped the Mormon and California Trails, and climbed into the Rocky Mountains. The next landmark is Independence Rock and the Sweetwater River.

“Stopped for dinner opposite Independence Rock. It is a great curiosity, but we were so tired that we could not go to the top of it. It is almost entirely covered with names of emigrants.” Cecelia E. Adams, 1852

At South Pass, the Emigrant Trail crossed the Continental Divide and proceeded into present-day Utah toward Fort Bridger. It was an emotional milestone. The weary emigrants had traveled over 900 miles.

“...this evening, with the sun, we passed from the Eastern to Western America....” William Marshall Anderson, 1834

The Oregon Trail turned northwest towards Fort Hall, passing into present-day Idaho, a segment later bypassed by cut-off routes. Meeting the Snake River, the route forked southward to the California Cut-Off, northward toward the Columbia River. It was here, at a mythic trail signpost, that the fundamental qualities of Oregon Pioneers were determined, some have theorized. After the discovery of gold in California in 1849, the majority of travelers took the southern route. Passing into present-day Oregon, the Oregon Trail came to Fort Boise, and continued through the Blue Mountains.

“Last night I put my cloths in water & this morning finished washing before breakfast. ... This is the third time I have washed since I left the states, or home.... Once at Fort Williams (Laramie) & at Rendezvous (Green River).” Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, 1836

The first years of the Oregon Trail migrations in 1841 and 1842 landed at Fort Walla Walla, where the emigrants rafted the Columbia River downstream. Later years landed at The Dalles, where it was possible to obtain flat-bottomed boats from the British to transport belongings to Fort Vancouver and on to Oregon City with the assistance of Dr. John McLoughlin, who was in charge of the Columbia Fur District of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Barlow Road opened in 1846, providing an access to the Willamette Valley around Mt Hood. The final descent down Laurel Hill was a difficult ordeal for impoverished nomads, but an improvement over the hazardous Columbia River portage. Also in 1846 the Applegate Trail established a route into the southern Willamette Valley from the California Trail.

The years 1846 to 1855 saw the greatest traffic on the Oregon Trail. Even after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, the Oregon Trail saw continued use until 1920. Undaunted by the Depression and the Great Recession, the hopeful influx of humanity, generations deep, streams into the Willamette Valley, joined by artists and writers reinventing the Oregon Mystique. West of Ella, in Morrow County Oregon, the trail can still be seen like a phantom on the rolling plains. Imagine the thoughts of those who had traveled 2000 miles to the sunset frontier. Will there be a place for the pioneers of tomorrow, or were we born 200 years too late? The images of heroic people reside proudly on the pages of history, gone but not forgotten.

The above story was written and submitted to us by J.D. Adams. You can send him a comment or read other stories by J.D. Adams

Shining with utopian beauty, Oregon is a beacon for those seeking to find their own way to freedom. Looming large is the legacy of the Oregon Trail that defines an unfolding story. In 1848, William Lysander Adams was one of hundreds of emigrants trekking westward that year. He packed his library across the Oregon Trail, and descended from the flanks of Mt. Hood on the Barlow Road into the Willamette Valley to become a pioneer preacher, a teacher, and later a statesman. What made Oregon home for the early pioneers is still a motivating force to later generations; the solitude of the countryside, never far from the sound of water. In the fertile valleys, windy fields and rolling oak savanna, dark grottos of greenery bristle in a patchwork shaped by ancient fires. On the horizon, the Cascades are rimmed in snow, thrusting glaciers into the clouds. The wind carries the promise of autumn on long summer days, mixed with the soft music of the river gliding toward the sea. It is this picture of paradise that keeps the dream alive.

The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolutionary War with Britain, extending the boundaries of the Unites States to the Mississippi River, and pushing the frontier into the Midwest. Mountain Men seeking beaver pelts were among the first to penetrate the Oregon Territory before 1841, followed by Missionaries. An expanding population and the need for economic and religious freedom set the stage for the Oregon Trail migration beginning in 1841-1843. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson organized the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804 to explore the areas west of the Rocky Mountains, including what was known as the Oregon Country. In the Oregon Treaty of 1846, the British ceded the Oregon Country to the United States, and it became the Oregon Territory in 1848 by an act of Congress. The Donation Land Claim Act, which granted free land in the Oregon Territory, was enacted by Congress in 1850.

The town of Independence, strategically located on the Missouri River and the Santa Fe Trail, was the starting point for many emigrants on the Oregon Trail. In later years, overuse and a cholera outbreak in Independence led to jumping-off places farther up the Missouri River gaining popularity, such as Westport, Liberty, St. Joseph, Weston, and Council Bluffs. Oregon Trail Pioneers generally followed the Santa Fe Trail into Kansas until a fork in the trail appeared; graced by a modest sign that cast the emigrants into the journey of a lifetime with only these words, “Road to Oregon”.

“My sister and I ascended to the summit of a hill and with the aid of a spy-glass took a farewell view of St. Joe. and the United States. Abigail Jane Scott, 1852”

The iconic covered wagons of the Old West are one of the most revered images in American history. Inspired artists of the Oregon Trail such as Albert Bierstadt have captured the wagon trains with a palette of light and intimate landscapes that invited exploration. The prairie schooner of the Oregon Trail was a specially adapted version of the mover’s wagons that found favor with the settlers of the eastern states of 1783 in progressing distances of two hundred miles or less. The typical Oregon Trail wagon was half the size of a Conestoga wagon at roughly ten feet in length, although a good percentage were actually sturdy farm wagons outfitted with a cloth cover, made often of hemp, and waterproofed with linseed oil.

The well-made wagon employed a box and wheels of hardwoods including oak, elm, ash, and ribs of hickory to support the canvas top. The rear wheels were rather large; almost 6 feet tall, the front wheels were made smaller for easier turning, and all rimmed in iron. The wheel hubs were conical and also reinforced with iron, part of an axle and pivoting frame that was flexible and lightweight. On one side of the wagon was a water bucket, on the other side a toolbox. A lever for braking was accessible, and a trusty pail of grease swung from the rear axle for maintenance of dry bearings.

In the midst of the overland migrations, guides for the traveler became popular, such as The Prairie Traveler Handbook printed in 1859. It advised to be taken for each grown person on the Oregon Trail: “150 lbs. of flour, or its equivalent in hard bread, 25 lbs. of bacon or pork, and enough fresh beef to be driven on the hoof to make up the meat component of the ration; 15 lbs. of coffee, 25 lbs. of sugar, also a quantity of yeast powders for making bread, and salt and pepper.” These are the chief articles of subsistence, to be used with economy and reserved for the western half of the journey. Mountain Men and prairie travelers alike could subsist on foods borrowed from the Native Americans, as described from the guidebook, “Pemmican, which constitutes almost the entire diet of the Fur Company's men in the Northwest is prepared as follows: The buffalo meat is cut into thin flakes, and hung up to dry in the sun or before a slow fire; it is then pounded between two stones and reduced to a powder; this powder is placed in a bag of the animal's hide, with the hair on the outside; melted grease is then poured into it, and the bag sewn up. It can be eaten raw, and many prefer it so. Mixed with a little flour and boiled, it is a very wholesome and exceedingly nutritious food, and will keep fresh for a long time.” Fruits and vegetables which were first pressed and then dried were also found on the plains to be quite flavorful when rehydrated. Another staple from the southwest was cold flour, a mixture of corn meal, sugar, and cinnamon, which could be mixed with water for a quick meal.

“Independence is a handsome flourishing town with a high situation.... The Emigrants were encamped in every direction for miles around the place awaiting the time to come for their departure. Such were the crowded condition of the streets of Ind by long trains of ox teams, mule teams, men with stock for sale, and men there to purchase stock that it was all most impossible to pass along....” James A. Pritchard, 1849

The trip to the Oregon Country usually began on a high note, with socializing and sightseeing, and then settled into the daily routines; on the trail by 7, a cold lunch at 12, progress was 15 miles on a good day. The ride in the wagons was rather bumpy so most preferred to walk. Alcove Springs was one of the first landmarks, a rock formation next to the Big Blue River, where many emigrants etched their names. From Kansas the Trail angled through Nebraska and encountered the Platte River at Fort Kearney. The Platte would be the guiding influence through the plains, through Ash Hollow, where wagon ruts are still visible, and past the evocative Courthouse Rock. Unfortunately, through this spectacular scenery the slow-moving water of the Platte River contributed to the spread of cholera, which claimed the lives of many travelers on the trail from severe dehydration.

After another fourteen miles is a landmark known as Chimney Rock, perhaps the most well-known spire of the American Midwest, now eroded somewhat from its former heroic proportions.

“...if a traveler were not convinced that he is journeying through a desert where no other dwellings exist ... he would be induced to believe them so many ancient fortresses or Gothic Castles, and with a little imagination, based upon some historical knowledge, he might think himself transported amid the ancient mansions of knight errantry ...” Fr. Pierre-Jean DeSmet, S.F., 1841

“We are now in sight of ... Chimney Rock ... which can be seen at the distance of thirty miles. It is two miles from the river, ...and from its peculiar form and entire isolation, is one of the most notorious objects on our mountain march.” William Marshall Anderson, 1834

The emigrants crossed into present-day Wyoming and passed by Fort Laramie on the way to Emigrant Gap, where the Oregon Trail overlapped the Mormon and California Trails, and climbed into the Rocky Mountains. The next landmark is Independence Rock and the Sweetwater River.

“Stopped for dinner opposite Independence Rock. It is a great curiosity, but we were so tired that we could not go to the top of it. It is almost entirely covered with names of emigrants.” Cecelia E. Adams, 1852

At South Pass, the Emigrant Trail crossed the Continental Divide and proceeded into present-day Utah toward Fort Bridger. It was an emotional milestone. The weary emigrants had traveled over 900 miles.

“...this evening, with the sun, we passed from the Eastern to Western America....” William Marshall Anderson, 1834

The Oregon Trail turned northwest towards Fort Hall, passing into present-day Idaho, a segment later bypassed by cut-off routes. Meeting the Snake River, the route forked southward to the California Cut-Off, northward toward the Columbia River. It was here, at a mythic trail signpost, that the fundamental qualities of Oregon Pioneers were determined, some have theorized. After the discovery of gold in California in 1849, the majority of travelers took the southern route. Passing into present-day Oregon, the Oregon Trail came to Fort Boise, and continued through the Blue Mountains.

“Last night I put my cloths in water & this morning finished washing before breakfast. ... This is the third time I have washed since I left the states, or home.... Once at Fort Williams (Laramie) & at Rendezvous (Green River).” Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, 1836

The first years of the Oregon Trail migrations in 1841 and 1842 landed at Fort Walla Walla, where the emigrants rafted the Columbia River downstream. Later years landed at The Dalles, where it was possible to obtain flat-bottomed boats from the British to transport belongings to Fort Vancouver and on to Oregon City with the assistance of Dr. John McLoughlin, who was in charge of the Columbia Fur District of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Barlow Road opened in 1846, providing an access to the Willamette Valley around Mt Hood. The final descent down Laurel Hill was a difficult ordeal for impoverished nomads, but an improvement over the hazardous Columbia River portage. Also in 1846 the Applegate Trail established a route into the southern Willamette Valley from the California Trail.

The years 1846 to 1855 saw the greatest traffic on the Oregon Trail. Even after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, the Oregon Trail saw continued use until 1920. Undaunted by the Depression and the Great Recession, the hopeful influx of humanity, generations deep, streams into the Willamette Valley, joined by artists and writers reinventing the Oregon Mystique. West of Ella, in Morrow County Oregon, the trail can still be seen like a phantom on the rolling plains. Imagine the thoughts of those who had traveled 2000 miles to the sunset frontier. Will there be a place for the pioneers of tomorrow, or were we born 200 years too late? The images of heroic people reside proudly on the pages of history, gone but not forgotten.

The above story was written and submitted to us by J.D. Adams. You can send him a comment or read other stories by J.D. Adams